What is all the fuss about essere and avere in Italian? Why do we bring up this topic so often in our grammar lessons? Essere and avere have their own meanings, be and have, but they are also used to form compound tenses.

What is a compound tense? The English present perfect, for example: I have done. Have is an auxiliary here, it helps or supports the verb to do. English has many auxiliaries, but to form compound tenses it uses have. In Italian, instead, we can use have, avere, or be, essere. So we say Io ho fatto and Io sono andato. We cannot say *Io ho andato, it would sound awful! But how to choose? There are a few rules that can help us remember.

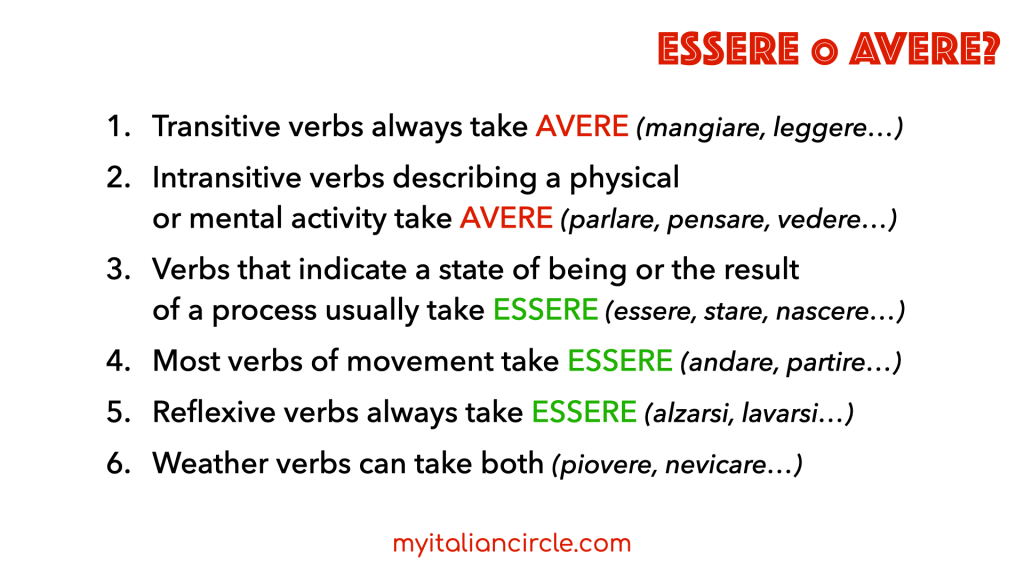

Regola! The basic rule is that transitive verbs always form compound tenses with avere:

- Ho organizzato una mostra al museo e ho fatto tutto io. I set up an exhibition at the museum and I did it all myself.

Una mostra and tutto are the objects of organizzare and fare, respectively, therefore these are transitive verbs that form compound tenses with avere.

Now, what is a transitive verb? It’s a verb that makes the action transition to a direct object. There is something or someone that receives the action of the verb. How to figure out if a verb is transitive? If our sentence answers the question “Chi?” or “Che cosa?”, who or what, we have a transitive verb, and we form compound tenses with avere.

Io leggo un libro. I read a book. This is the present tense.

Io leggo – che cosa? – un libro.

Libro is the object, so leggere is transitive, the passato prossimo is:

Io ho letto un libro. Auxiliary avere. Easy.

You might end up thinking that intransitive verbs, those that cannot take an object, always use essere. Yes and no, it depends on the type of verb.

Regola! Intransitive verbs describing a physical or mental activity take avere: ho respirato (I breathed), ho pensato (I thought), ho parlato (I spoke).

What about essere? Essere indicates a state, and these types of verbs take the auxiliary essere: sono stato.

- Sono stato molto impegnato con il lavoro. I have been very busy with work.

Regola! So, remember: among the verbs that usually take essere are those that indicate a state of being or the result of a process, such as rimanere and restare (stay), diventare (become), nascere (be born).

- Paolo Sorrentino è nato a Napoli, io sono nata a Bologna. Paolo Sorrentino was born in Naples, I was born in Bologna.

- Dove sei stata ieri? Sono rimasta a casa. Where were you yesterday? I stayed home.

So, there are two main rules to keep in mind:

- Transitive verbs take avere.

- Verbs that indicate a state of being or the result of a process usually take essere.

Regola! Let’s move on and add one more piece to the puzzle: the vast majority of verbs of movement also take essere, so a sentence like: yesterday I went to Venice in Italian is Ieri sono andata a Venezia.

Andare is a verb of movement, so we have to use essere: io sono andata, Luca è andato, le ragazze sono andate and so on.

You may have noticed an additional complication here: when the auxiliary is essere, the past participle agrees with the subject. Luca, masculine singular: è andato; le ragazze, the girls, feminine plural: sono andate. This does not happen with avere.

Now, this rule seems simple enough, but watch out! A few verbs of movement take avere, such as camminare and viaggiare, so we say ho viaggiato and ho camminato. Rule of thumb: when the verb indicates only a movement, the auxiliary is avere; when it expresses a movement from a place or to another, then it takes essere. Compare:

Sono partita ieri (even if the place is not expressed, I must have come from somewhere), ho viaggiato tutta la notte e sono arrivata a casa alle 16.00. I left yesterday, I travelled all night and I got home at 4pm.

Compare again: Ho corso per due ore – I ran for two hours (here I’m focusing on the movement) and Sono corsa a casa – I ran home (here I have a destination). Correre can take both avere and essere, and it’s not the only verb that can do this!

Regola! Now, to cheer you up, let’s add a rule that’s always true: reflexive verbs always take essere. These are verbs whose action reflects on the subject or something that belongs to it, like alzarsi and lavarsi:

- Marco si è alzato alle sette. Marco got up at seven.

- Io mi sono lavata i denti dopo colazione. I brushed my teeth after breakfast.

- I ragazzi non si sono lavati le mani. The boys did not wash their hands.

What about the weather? Freedom! For weather verbs, use either essere or avere:

- Ha piovuto tutta la notte. / È piovuto tutta la notte. It rained all night.

- Ieri è nevicato. / Ieri ha nevicato. It snowed yesterday.

Finally, we need to remember that some verbs are not intrinsically transitive or intransitive, but can be used in one way or the other: they may have an object or not, such as cominciare, finire, iniziare, terminare, vivere, aumentare, cambiare. For example:

- Il professore ha cominciato (transitive use) la lezione (direct object).

The professor started the lesson. Transitive verbs form compound tenses with avere. - La lezione è cominciata (intransitive use, no direct object).

The lesson started. Intransitive verbs form compound tenses with essere.

Let us sum it all up:

How to remember all this? Learning the rules is a good starting point, but you also need to read and listen to as much Italian as you can, paying attention to auxiliaries when you read your favourite Italian magazine, Italian website, or when you listen to your favourite Italian TV programme. This way, you will naturally pick up these patterns. Ultimately, you will figure out what sounds right and what sounds wrong. And whenever in doubt… check the dictionary! It will tell you which auxiliary to use.

A presto!

Related video lessons:

- Il passato prossimo – Essere o avere?

- Common uses of essere and avere in Italian

- Learn Italian with Art 3 – Essere o avere?

Leave a Reply