Dante and the Divine Comedy

Who was Dante?

Dante Alighieri (1265 – 1321) is universally considered to be the most important writer in the Italian language, and one of the greatest poets of all times. His major work, which he called Comedia and later became Divina Commedia, is still read, translated, and commented upon after 700 years. At the time, Latin was still the language of choice for important literary works, and yet he decided to employ a different style: remissus est modus et humilis, quia locutio vulgaris in qua et muliercule comunicant – the style is unstudied and humble, because it is in the vernacular speech, in which even women talk. But Dante does not only adopts the vernacular language, he also recreates and expands it, moulding and bending it to his literary needs and inventing bold new words.

Dante's masterpiece was widely disseminated and praised while he was still alive, but he was a haughty, ambitious man who also yearned for recognition as a highbrow scholar. His exile from Florence, his home town, was another cause of much suffering and distress. As we recount in this video, he spent several years in Verona, where he was forced to accept the salty bread of the local lords, the Scaligeri.

At the time Italy was divided into several kingdoms and city-states, some loyal to the Pope and others to the Holy Roman Emperor. In Florence, these two factions – Guelphs and Ghibellins, respectively – would tear the city apart, fighting for power and alternating as its leaders for centuries. The former further divided into White Guelphs, who opposed Pope Bonifacio VIII, and Black Guelphs, who continued to support the papacy. Dante, a White Guelph, was exiled in 1302 when the Black Guelphs took control of Florence, and never returned to his unloving mother. His remains are still buried in Ravenna, where he died in 1321, probably after contracting malaria.

Find your way through the Divine Comedy

The Comedy was written approximately between 1308 and 1320, during Dante’s exile, and it describes his imaginary journey through Hell, Purgatory and Paradise, from damnation through penance to salvation. Dante calls it a comedy because it has a happy ending – the happiest that man can ever imagine: the sight of God himself and the perfect enjoyment of his Love.

Dante sets his journey in the past, in the days around Easter of the year 1300. Thanks to this device, everything he writes about the following years sounds like a prophecy. On the morning of the 25th of March, while trying to find the right way out of a dark forest (selva oscura), Dante is confronted by three dangerous beasts: una lonza – a leopard or lynx (symbol of lust), un leone – a lion (symbol of pride), una lupa – a she-wolf (symbol of greediness). The latter frightens him so, that he is forced back into the darkness.

Here the actual journey begins. Rescued and lead by the soul of Latin poet Virgil, author of the Aeneid, Dante enters the eternal gate of Hell, where he reads the famous inscription: Lasciate ogni speranza, voi ch’entrate – All hope abandon, ye who enter in! The first part of the Comedy is the one that most people know and love. Gruesome, colourful, grotesque, even comical: Dante’s descent into the funnel-shaped gorge of Hell and the many striking characters that he encounters on the way are sure to leave an impression on the reader.

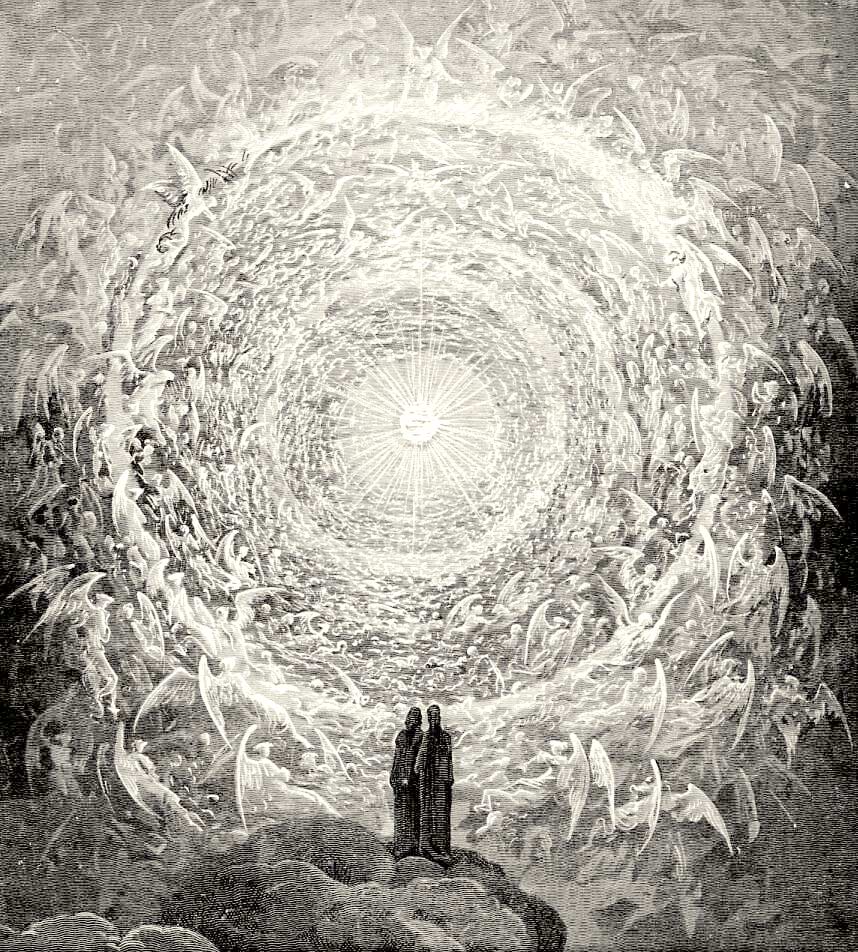

But don’t underestimate the other two thirds of the work. While he climbs the mountain of Purgatory, Dante’s poetry becomes more lyrical and noble, and it reaches its highest moments as he enters the Paradise and ascends through the heavens, this time lead by Beatrice, his childhood love, who represents theology, faith, and grace. The souls that he encounters in Purgatory are still very much human, and even in Paradise not all is black and white. Alongside the great saints of the Church, he also meets more worldly characters, such as those who inhabit the first three spheres: in spite of their deficiencies, they can still enjoy the bliss of Heaven.

Interestingly, all three parts of the Divine Comedy end with the word stelle (stars). E quindi uscimmo a riveder le stelle – Thence we came forth to rebehold the stars: as Dante emerges from the darkness of Hell and finds himself on the beach of the island of Purgatory, he can finally see the sky again. We read the beginning of the Purgatory on the first Dante Day, on 25 March, 2020: listen to it here for a glimpse of the enchanting sound of Dante's poetry. Click here to download the text of this reading with English translation.

A taste of the Comedy

In the third canto, Dante enters the gate of Hell and sees the souls of people who took no sides, and were neither for good or evil (ignavi, the morally indolent); they are so vile that they don’t even deserve a place in Hell. At the end of the canto, Dante and Virgil cross the river Acheron on Charon’s boat, and Dante faints, overwhelmed by the experience. A thunder awakens him at the beginning of the fourth canto.

Ruppemi l’alto sonno ne la testa

un greve truono, sì ch’io mi riscossi

come persona ch’è per forza desta;e l’occhio riposato intorno mossi,

dritto levato, e fiso riguardai

per conoscer lo loco dov’io fossi.Vero è che ’n su la proda mi trovai

de la valle d’abisso dolorosa

che ’ntorno accoglie d’infiniti guai.Oscura e profonda era e nebulosa

tanto che, per ficcar lo viso a fondo,

io non vi discernea alcuna cosa."Or discendiam qua giù nel cieco mondo",

cominciò il poeta tutto smorto.

"Io sarò primo, e tu sarai secondo".

Broke the deep lethargy within my head

A heavy thunder, so that I upstarted,

Like to a person who by force is wakened;And round about I moved my rested eyes,

Uprisen erect, and steadfastly I gazed,

To recognise the place wherein I was.True is it, that upon the verge I found me

Of the abysmal valley dolorous,

That gathers thunder of infinite ululations.Obscure, profound it was, and nebulous,

So that by fixing on its depths my sight

Nothing whatever I discerned therein."Let us descend now into the blind world,"

Began the Poet, pallid utterly;

"I will be first, and thou shalt second be."

Here Dante begins the descent into the bowels of the earth and through the circles of Hell, lead by his guide Virgil.

English translation by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1867.

Glossary

- Cantica (pl. cantiche): each of the three parts of the Comedy – Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso.

- Canto (pl. canti): each of the chapters of a cantica; 34 for Hell, 33 each for Purgatory and Paradise, for a total of 100 canti.

- Terzina (pl. terzine): a three-line stanza or strophe.

- Endecasillabo (pl. endecasillabi): a line made of 11 syllables.

- Terza rima: an interlocking three-line rhyme scheme – ABA, BCB, CDC, and so on.

- Contrappasso: the principle according to which a sinner receives a punishment similar or opposite to the sin itself.

- Cerchio (pl. cerchi): each of the nine concentric divisions of Hell, where damned souls are grouped according to their sin.

Other works by Dante

- Il Fiore

- Detto d’amore

- Le Rime

- Vita nova

- Convivio

- De vulgari eloquentia (Latin)

- De Monarchia (Latin)

Further readings

For more in-depth information about this topic, we recommend:

Benedetto Croce, The Poetry of Dante (English translation 2019)

Guy P. Raffa, Dante’s Bones: How a Poet Invented Italy (2020)

Guy P. Raffa, The Complete Danteworlds: A Reader's Guide to the Divine Comedy (2009)

Barolini, Storay (eds.), Dante For the New Millennium (2003)

Teodolinda Barolini, Dante and the Origins of Italian Literary Culture (2009)

At no additional cost to you, we will earn a commission if you make a purchase on Amazon after clicking through the links listed above. This will help support this Website.